Contents

- 1 Ancient Roots: The First Wave of Historical Explorers

- 2 The Age of Sail: How Maritime Historical Explorers Redefined the World Map

- 3 Conquering Continents: Land and Ice-Based Historical Explorers

- 4 Beyond the Horizon: Modern Historical Explorers of the 20th and 21st Centuries

- 5 Legacy and Re-evaluation: The Complex Impact of Historical Explorers

- 6 FAQ: Common Questions About Historical Explorers

- 7 Conclusion

- 8 References

Ancient Roots: The First Wave of Historical Explorers

Long before the famed Age of Discovery, the thirst for knowledge, trade, and expansion propelled early civilizations across unknown waters and lands. These ancient trailblazers were the original historical explorers, laying the groundwork for millennia of discovery to come. Their motivations were often pragmatic—seeking resources like tin, amber, and new fishing grounds—but their impact was profound, creating the first threads of a connected world.

The Phoenicians, master mariners of the ancient Mediterranean, are a prime example. From their home base in modern-day Lebanon, they established a vast trading network that stretched from the shores of the Levant to the coasts of Spain and possibly even the British Isles. Around 600 BCE, according to the Greek historian Herodotus, a Phoenician expedition commissioned by Egyptian Pharaoh Necho II is said to have circumnavigated Africa, a feat that would not be repeated for over 2,000 years. While direct archaeological proof remains elusive, their known seafaring prowess makes the account plausible and marks them as pioneers among historical explorers.

Simultaneously, in the Pacific, Polynesian navigators were undertaking some of the most remarkable voyages in human history. Using sophisticated knowledge of star patterns, ocean swells, and bird migration, they systematically settled a vast triangle of ocean covering islands from Hawaii to Easter Island to New Zealand. This was not accidental drifting but deliberate, masterful exploration that stands as a testament to human ingenuity.

Analysis: Knowledge as a Survival Tool

What distinguishes these early explorers is that their methods were born from deep ecological and astronomical knowledge passed down through generations. For the Polynesians, the canoe (wa'a) was not just a vessel but a microcosm of their society, and the ocean was not a barrier but a highway mapped by memory and observation. For these ancient historical explorers, exploration was inextricably linked to survival and cultural expansion, a stark contrast to the later, often state-sponsored, quests for conquest and glory.

The Age of Sail: How Maritime Historical Explorers Redefined the World Map

The period from the 15th to the 17th century, often called the Age of Discovery, witnessed an unprecedented explosion of maritime exploration. Driven by a potent mix of economic ambition, religious zeal, and burgeoning nationalism, European nations sent fleets across the globe. The historical explorers of this era did not just fill in the blanks on the map; they redrew it entirely, connecting hemispheres and setting in motion the forces of globalization and colonialism that still shape our world today.

Pioneers of a New World Order

Christopher Columbus’s 1492 voyage across the Atlantic, sponsored by Spain, is arguably the most famous. While aiming for Asia, he encountered the Americas, an event that triggered a massive transfer of plants, animals, cultures, technologies, and diseases known as the Columbian Exchange. His voyages opened the door for widespread European colonization of the "New World."

Following him, Portuguese explorer Vasco da Gama successfully navigated around Africa to reach India in 1498, establishing a direct sea route to the lucrative spice markets of the East. This broke the Venetian and Ottoman monopoly on the overland trade routes. A few decades later, the expedition led by Ferdinand Magellan achieved the first circumnavigation of the Earth (completed by Juan Sebastián Elcano after Magellan's death), proving definitively that the world was round and far larger than previously imagined.

Analysis: A Double-Edged Sword of Progress

The achievements of these historical explorers were monumental from a European perspective. They introduced new navigation techniques, like the use of the astrolabe and quadrant, and spurred advancements in cartography and shipbuilding. However, this era of discovery came at an immense cost. The arrival of Europeans led to the conquest of empires like the Aztec and Inca, the decimation of Indigenous populations through violence and disease, and the horrors of the transatlantic slave trade. Analyzing this period requires a dual focus: celebrating the incredible feats of human endurance and navigation while soberly acknowledging the devastating consequences for the non-European world.

Conquering Continents: Land and Ice-Based Historical Explorers

While the oceans captured the imagination, the vast interiors of continents and the frozen poles presented their own formidable challenges. During the 18th and 19th centuries, the focus of exploration often shifted inward, driven by scientific curiosity, national expansion, and the sheer desire to be the first to stand on an uncharted spot. These land-based historical explorers were surveyors, scientists, and diplomats as much as they were adventurers.

Mapping the Wilderness

![]()

In North America, the Lewis and Clark Expedition (1804-1806) was commissioned by President Thomas Jefferson to explore the newly acquired Louisiana Purchase. Their journey to the Pacific coast and back provided invaluable information about the geography, biology, and inhabitants of the American West, paving the way for westward expansion.

In Africa, figures like David Livingstone and Henry Morton Stanley ventured deep into the continent's interior, tracing the courses of the Zambezi and Congo rivers. While their work contributed significantly to Western knowledge of African geography, it was also deeply enmeshed with missionary work and the "Scramble for Africa" that led to European colonial rule.

The Race to the Poles

The early 20th century was defined by the heroic and often tragic "Race to the Poles." The quest to reach the North and South Poles was a matter of intense national pride. Norwegian explorer Roald Amundsen, using meticulous planning and learning from Inuit survival techniques, led the first expedition to successfully reach the South Pole in December 1911. His British rival, Robert Falcon Scott, arrived a month later only to perish with his entire party on the return journey, their story becoming a powerful, albeit tragic, legend of endurance.

Analysis: Science and Nationalism Hand-in-Hand

The great continental and polar expeditions were often government-funded scientific endeavors. Unlike some earlier voyages focused purely on wealth, these journeys cataloged flora and fauna, mapped geological formations, and gathered meteorological data. Yet, this scientific pursuit was rarely pure. For these historical explorers, planting a flag was as important as collecting a specimen. Their journeys were direct instruments of imperial and national ambition, solidifying territorial claims and projecting power into the world's last remaining blank spaces. The complex impact of these expeditions reflects this dual nature of progress and conquest.

Beyond the Horizon: Modern Historical Explorers of the 20th and 21st Centuries

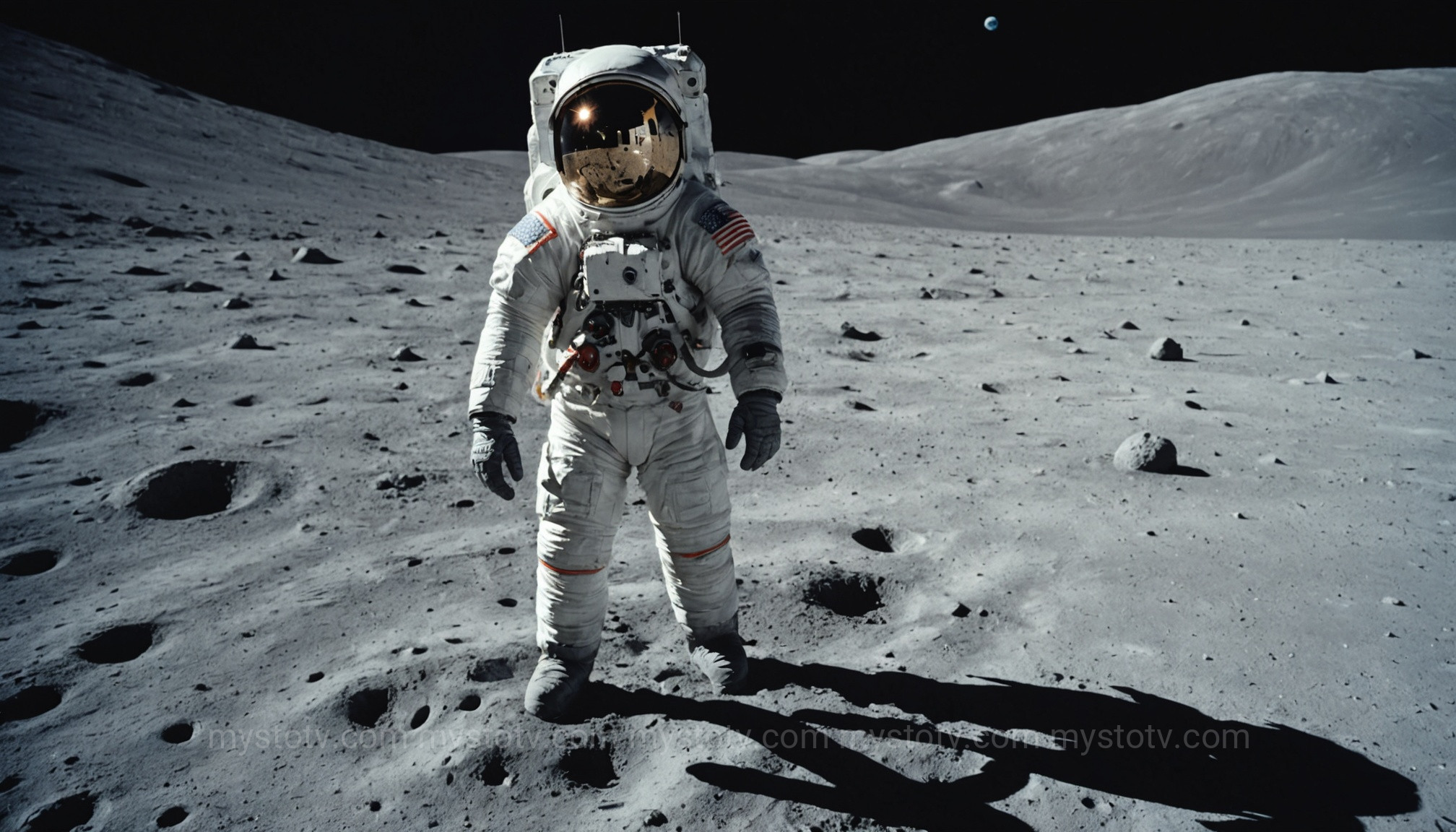

As the 20th century progressed, the last terrestrial frontiers were conquered. The spirit of exploration, however, did not wane; it simply turned its gaze upward to the cosmos and downward to the abyssal depths of the ocean. The new breed of historical explorers were astronauts, aquanauts, and scientists, using cutting-edge technology to venture into environments far more hostile than any faced before.

The Final Frontier: Space

The Cold War space race between the United States and the Soviet Union ushered in the age of cosmic exploration. Soviet cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin became the first human in space in 1961, followed by American astronaut Neil Armstrong's "one giant leap for mankind" as the first person to walk on the Moon in 1969. These moments, broadcast to a captivated global audience, fundamentally changed humanity's perspective of its place in the universe.

The Deepest Depths: The Ocean

At the same time, explorers pushed into the crushing pressures of the deep sea. In 1960, Jacques Piccard and Don Walsh descended to the bottom of the Mariana Trench, the deepest known point on Earth, in the bathyscaphe Trieste. Later, oceanographers like Robert Ballard would use remotely operated vehicles (ROVs) to explore hydrothermal vents teeming with strange life and to discover historic shipwrecks like the Titanic, opening a new field of deep-sea archaeology.

Analysis: The Shift from Geography to Science

Modern exploration is defined by technology and a focus on scientific data. While national pride is still a factor, the primary goal is knowledge—understanding planetary formation, searching for extraterrestrial life, or discovering new species and ecosystems that could lead to medical breakthroughs. These modern historical explorers are rarely lone adventurers but part of vast, collaborative scientific teams. Their frontier is not a physical place on a map but the boundary of human knowledge itself.

Legacy and Re-evaluation: The Complex Impact of Historical Explorers

The legacy of historical explorers is a tapestry woven with threads of brilliant achievement and profound tragedy. It is impossible to study their histories without confronting a dual narrative. On one hand, their courage expanded human knowledge, connected disparate cultures, and drove technological innovation. On the other, their arrivals often heralded disease, war, exploitation, and the erasure of entire cultures. A modern, critical perspective requires us to hold both these truths at once.

Contemporary analysis, particularly from post-colonial and Indigenous viewpoints, has rightly challenged the heroic, Eurocentric narratives that dominated history books for centuries. The term "discovery" itself is now questioned, as it inherently ignores the millions of people who already inhabited and intimately knew the lands being "discovered." Recognizing the full context—the glory and the suffering, the bravery and the brutality—is essential to understanding how the journeys of these trailblazers truly changed our world, for better and for worse.

FAQ: Common Questions About Historical Explorers

Who is the most significant historical explorer?

This is a subjective question with no single answer. For sheer global impact, Christopher Columbus is a strong candidate, as his voyages initiated permanent contact between the Eastern and Western Hemispheres. For navigational skill and proving the Earth's true scale, Ferdinand Magellan's expedition is paramount. For expanding the human habitat across a vast ocean, ancient Polynesian navigators are unparalleled. The "most significant" depends entirely on the criteria: impact, distance, scientific contribution, or pure audacity.

What were the primary motivations for historical explorers?

Motivations evolved over time but can often be summarized as "Gold, God, and Glory." Gold represents the desire for wealth, whether through spices, precious metals, or new trade routes. God signifies the religious drive, from spreading Christianity to missionary work. Glory encompasses the quest for personal fame, national pride, and the simple, powerful human desire to be the first to see what lies beyond the horizon. Scientific curiosity became a more dominant motivator in later centuries.

Early explorers used a combination of techniques. Celestial navigation was key, using instruments like the astrolabe, quadrant, and later the sextant to measure the angle of the sun or stars above the horizon to determine latitude. They used a magnetic compass for direction and practiced "dead reckoning"—calculating their position by estimating their course and speed from a previously determined position. This was supplemented by detailed logbooks, knowledge of winds and currents, and rudimentary maps that became more accurate with each successive voyage.

Conclusion

From the ancient Polynesians reading the stars to modern astronauts gazing back at Earth, the story of humanity is a story of exploration. The journeys of historical explorers are far more than adventurous tales; they are the catalysts that connected continents, created global economies, and challenged our very conception of the world. While we must now critically evaluate their full impact, acknowledging both the triumphs and the tragedies they set in motion, we cannot deny their role as profound agents of change. The enduring spirit of these trailblazers—that innate human drive to push past the known and into the unknown—continues to inspire us to explore the new frontiers of science, technology, and thought that will shape the world of tomorrow.

References

- Herodotus. The Histories. (c. 440 BCE). (Book 4, Chapter 42 describes the Phoenician circumnavigation of Africa).

- Bergreen, Laurence. Over the Edge of the World: Magellan's Terrifying Circumnavigation of the Globe. William Morrow, 2003.

- Ambrose, Stephen E. Undaunted Courage: Meriwether Lewis, Thomas Jefferson, and the Opening of the American West. Simon & Schuster, 1996.

- National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA). "Apollo 11 Mission Overview." Accessed October 26, 2023. https://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/apollo/missions/apollo11.html